Coachella 2012 set the internet ablaze when Snoop Dogg closed out his headlining set by bringing out a “hologram” of the rapper Tupac Shakur. The reactions ranged from “creepy” to “astonishing”—but all entertainment veteran Martin Tudor could think was, “Now what?”

“They did two songs and that’s it?” says Tudor, whose extensive career has spanned doing lighting design for Broadway shows to running a talent management group and record label. “You teased me, but now I want to see a show.”

What people saw onstage seven years ago has actually been around for much longer—and, in fact, wasn’t even a hologram. Tupac’s performance was created by AV Concepts using CGI and the fundamentals of a 19th century illusion called Pepper’s Ghost. Madonna and the Gorillaz used it at the 2006 Grammys, as did Al Gore in 2007 to kick off Tokyo’s Live Earth benefit concert.

However, what Tudor saw wasn’t just some one-off gimmick. He believed there was potential to tap into something deeper with audiences and develop a sustainable business model.

“People are clamoring for nostalgia,” Tudor says. “I thought it was pretty cool to be able to see people that I never saw in my life. That’s what really dragged me in.”

In January 2018, Tudor, along with former Clear Channel CEO Brian Becker, announced the launch of Base Hologram, a production company for holographic performances. Although there are competitors in the space like Eyellusion and Hologram USA, Base has pulled away from the pack in securing the rights for top-tier acts including Roy Orbison, Buddy Holly, and opera diva Maria Callas. Last month, the company announced its biggest get to date with a Whitney Houston tour set for early 2020.

Tudor and Becker are tapping into a booming demand for live experiences that has helped the top 100 concert tours alone grow to more than $65 billion globally, according to Pollstar. In addition, the nostalgia market shows no signs of abating: Four of the top 10 touring artists in 2018 were “legacy acts”: The Eagles, Roger Waters, U2, and the Rolling Stones.

One of the main factors behind Base’s early success is its technology is a significant upgrade from Tupac’s Coachella cameo while also being nimble enough to allow for a relatively aggressive touring schedule. However, even with sharper graphics and the stamp of legitimacy that a tour like Houston’s may confer, Base still faces meaningful challenges. It not only has to prove that this nascent technology can help establish a new type of live entertainment, but it also has to do so amid the ethical questions that surround holographic performances of deceased celebrities.

Reanimating Pepper’s Ghost

Pepper’s Ghost was popularized by British scientist John Henry Pepper, who debuted his version in an 1862 stage production of Charles Dickens’s The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain. The basic mechanics involve a reflected image giving the illusion of someone or something in its physical form. For Tupac at Coachella, a live actor was made to look like Tupac using CGI. That performance was then projected downward on a reflective surface, which bounced the moving image onto a tightly pulled transparent foil screen.

It’s an effective illusion but not efficient for a touring schedule.

“There’s a lot of tension on the screen, like 1,200-pounds-per-inch kind of tension,” Tudor says. “So you have to set up an enormous structure around that to be able to deal with the tension on the screen. To do a full stage-size screen is doable. It’s just a big undertaking.” Base also records live actors with CGI mapping to create its stars.

The seminal development that has allowed Tudor to go beyond the legacy tech is when he found a company in the U.K. that develops a proprietary mesh screen that makes setting up and breaking down a set much faster. What’s also elevating Base’s productions is an Epson projector capable of producing 25,000 lumens of light (a standard 60-watt bulb produces about 800 lumens). Instead of the Pepper’s Ghost technique, Base projects directly onto the screen.

Base’s technology does have its limitations: There’s currently no way to project a volumetric image (which would represent a character in three dimensions), certain venue seats can’t be sold because of angle issues, projections can walk across the stage but can’t go up and down stairs, and so forth. However, none of the above stopped Base from producing more than 40 shows across the U.S., South America, Mexico, and Europe in 2018.

Read the case study, Holograms Changing the Landscape of the Live Theater Experience, or watch the video to learn more about Base Hologram’s use of Epson Pro L25000U laser projectors in their events.

Putting on a show

Working with technology that makes that kind of touring possible, the focus was then placed on creating an engaging, full-length production. Base’s parent company, Base Entertainment (which spun out Base Hologram) has 35 years of experience producing live shows and currently stages a number of Vegas-style spectaculars such as Magic Mike Live.

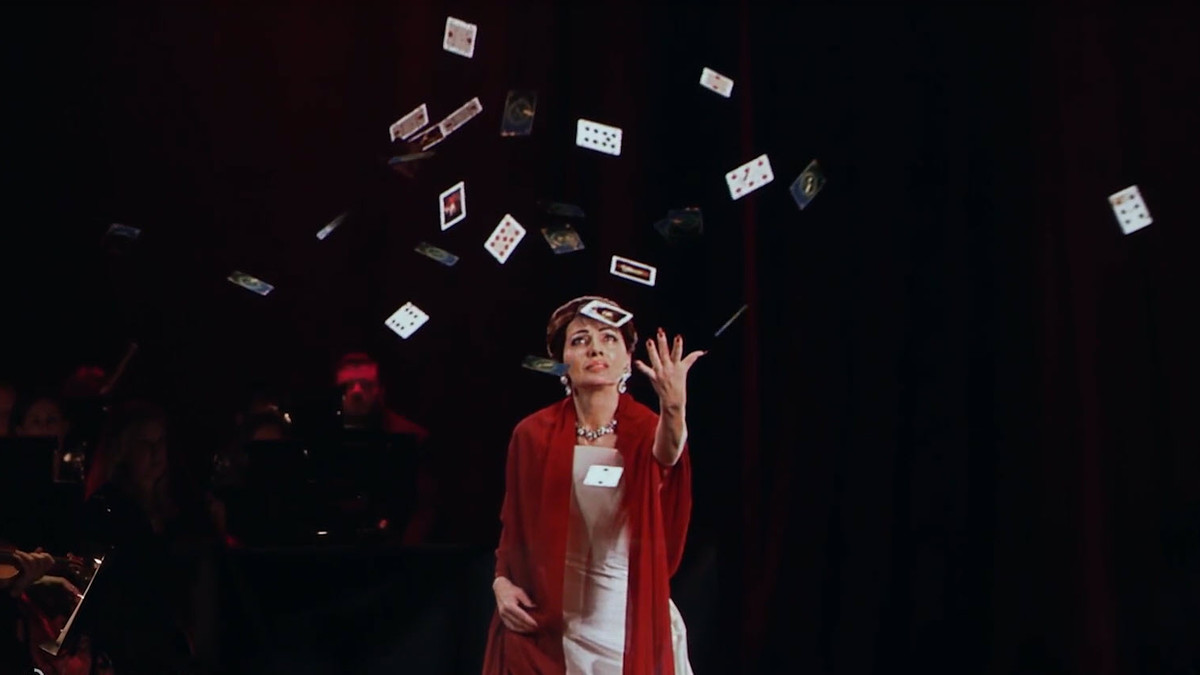

Like Pepper’s Ghost, Base’s performances are essentially just 2D recorded renderings. But one of the main draws for a live concert is just that—it’s live. Whether or not an artist is actually singing or using prerecorded vocals, you at least get to see them in person. Base incorporates live elements into its productions (for example, Maria Callas tours with a 50-piece orchestra), but Becker and Tudor are hoping to reframe the live experience in this particular context as something of a hybrid between a film and theater production.

“It’s a fully produced, scripted show. We’re not replicating a concert only. We are creating a concert experience,” Becker says. “You’re going to see the holographic image interacting with the band or with the conductor or making mistakes, getting flowers, whatever the case is. It’s all in the writing and the script and the choreography and the production.”

Adds Tudor: “Why do you go to the movies? You’re not seeing a live experience. Where else would you get that kind of experience where you’re seeing a representation of the artist, and hearing their actual voice with live accompaniment? You can’t get that at home.”

Base Hologram interactive concert performance with Roy Orbison. [Photo: Evan Agostini for Base Hologram]

Ethics test

It’s a fair argument that Base is ready to use against the questions fogging posthumous performances as its roster of artists continues to grow.

In order to create a production, Base, of course, must secure permission from an artist’s estate, as well as music rights from the record label. But at no point does the actual artist have a say in the matter. What’s more, it’s not like an audio or video recording that’s released after an artist dies. Holographic performances that create a likeness of an artist led music journalist Simon Reynolds to coin the phrase “ghost slavery.” At the time of Tupac’s Coachella performance, an op-ed in Billboard argued that “there exists a token of beauty in letting Pac’s music speak for itself, and not grafting a false image onto his classic sounds simply because we missed Tupac perform when he was alive and want to see him now.”

The more checkered the circumstances of an artist’s death, the more controversy there is about their hologram. Base’s upcoming Whitney Houston concert, for example, has been called “tacky and exploitive.” Dionne Warwick, legendary singer in her own right and Houston’s cousin, flat-out called the idea “stupid.” The Netflix series Black Mirror, ever the barometer for the implications of tech going too far, even weighed in on the topic in its newest season featuring Miley Cyrus as a pop star whose holographic image goes on tour after she’s hospitalized.

Tudor is far from fazed or surprised at the criticism. In fact, he weighted the initial touring schedules with more dates in Europe for this exact reason.

“Frankly, in Europe the audiences are a little bit more forgiving than they are here,” he says. “So we thought, let’s get our sea legs over there without being under the microscope of our United States press. There’s a general trend going all the way back to the beginnings of opera in Europe: People tend to follow what happens overseas here in their programming. So we thought also if we’re accepted over there, then it will follow here. It’s been true so far.”

“We’ve had detractors,” Becker acknowledges. “God, if we didn’t have detractors, we’re not trying hard enough, I guess. But overwhelmingly, we’ve had great, positive responses.”

Peter Lehman, director of the Center for Film, Media, and Popular Culture at Arizona State University and author of Roy Orbison: The Invention of an Alternative Rock Masculinity, has become something of a Orbison scholar, having seen him perform frequently from 1964 to 1988.

“Of course, no hologram concert can recreate the thrill of the live concerts, but that misses the important point of what a hologram concert can do,” Lehman says. “Most critics obsessed about the details of the hologram image, which in fact does not look much like Roy did. But the concerts were a great success because of the stunning sound quality, including hearing Roy’s voice with nearly the same beauty and power it had live.”

Lehman argues that holographic concert shouldn’t be seen as lesser versions of a live show or that they somehow undermine an artist’s legacy.

“Remember, everything Orbison ever recorded is left untouched by the hologram. Nothing is destroyed, but something new is added,” Lehman says. “People who are appalled by this should stay home, but stop worrying about the ruin of the music world as we know it.”

One of Base’s primary objectives is to brand the company’s offerings as premium and respectable entertainment. Earlier this year, Base put a hold on an Amy Winehouse concert in production, citing “unique challenges and sensitivities.”

“We’ve got to be authentic and respectful of the artists that we’re working with,” Becker says. “In the case of Amy, what we found is that there were a lot more complexities and sensitivities, because she was a great artist, but she had a difficult life and a tragic death. And we just were too early to do what we want to do with that.”

The future will be hologrammed

Sure, there will always be naysayers to the entire concept of holographic concerts, but advancements in technology have made the idea more attractive to some, particularly (and in many cases most importantly) to the tightly guarded estates of some of music’s biggest stars.

Back in 2016, the Houston estate pulled what was supposed to be a holographic duet between the singer and Christina Aguilera for a finale of The Voice, deeming the performance “not ready to air.”

“We were looking to deliver a groundbreaking duet performance for the fans of both artists,” the statement read. “Holograms are new technology that take time to perfect, and we believe with artists of this iconic caliber, it must be perfect. Whitney’s legacy and her devoted fans deserve perfection.”

Apparently, that time has come, in no small part to the careful considerations Base is taking. Celebrated choreographer and music video director Fatima Robinson was tapped to helm An Evening with Whitney. Having known Houston personally (and having helped with Tupac’s Coachella performance), Robinson says she wanted to get involved to make sure it was done properly.

“I think Whitney’s presence was with us when we were shooting, and I think her knowing that I was involved and her family was there would have made her proud,” Robinson says. “To me, this is about remembering Whitney’s body of work. And it’s just like putting on a DVD of her performance and enjoying it, except with this you really feel like she’s back on that stage in front of you. There is a whole generation, including my son, who never had the chance to see Whitney perform, and it was important to me that they get that chance. I think this is a great way to honor her work and let people fall in love with her again.”

Base Hologram interactive concert performance with Maria Callas. [Photo: Evan Agostini for Base Hologram]Base is aiming to roll out about two new shows a year, with the intention of expanding beyond just music concerts. There’s currently a project in the works with famed paleontologist Jack Horner to tour a dinosaur showcase across museums around the world. Tudor also mentions there’s a heavy focus on malls, “because they are all scrambling so they’re looking for things that will draw people in.”

Despite the collective decades of experience in entertainment between Tudor and Becker, they both admit that dealing in the hologram space is still uncharted territory.

“I’m pulling from my competitors,” Becker admits. “We’re all developing something new, and it’s very important to me that they are artistically and commercially successful.”

Michael Bierylo, chair of electronic production and design at Berklee College of Music, likens holographic performances now to consumers experiencing color television for the first time in the 1940s. “It’s hard to imagine 50 years from now,” he says. But that also leaves a lot of white-space innovation, which he believes can be filled by live performers adopting the technology to make it less of a novelty.

“Artists always seem to embrace whatever technology becomes available, and we would hope that their creativity will help provide a viable business model for the new technology,” Bierylo says. “We’re seduced by the uncanniness of seeing artists who have had meaning to our culture come back to life, but if that’s the only use of the technology, it’s not going to go far. It was great to hear Natalie Cole singing with her father, but that didn’t inspire a long-term trend.”

That’s certainly in Base’s purview, but ultimately Becker thinks holograms becoming widely accepted—both by audiences and the entertainment industry at large—is really just a matter of time.

“The art that we’re developing is really significant,” Becker says. “What we have to do is make sure that we continue to do that, and then, over time, we will not be considered a niche.”

This article was written by Kc Ifeanyi from Fast Company and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@newscred.com.